Written by : Umakant Sir (ex-Civil Servant & Mentor)

GenZ does not want to work endlessly, because their parents and grandparents did. And there is nothing wrong about it.

GenZ prefers meaningful work rather than “just hard work”.

The Debate of Work:

The question of how much one should work has re-emerged as a contentious public debate in recent times. Statements by business leaders such as Elon Musk, who advocates 80–100 hour workweeks, and N.R. Narayana Murthy, who called for a 70-hour workweek for India’s youth, have reignited discussions on productivity, national growth, and personal well-being.

At its core, the debate reflects a deeper conflict between industrial-era notions of sacrifice and post-industrial concerns for sustainability, dignity, and mental health.

Proponents of longer working hours argue from the standpoint of economic urgency and competitive pressure. For developing economies like India, they contend, rapid growth demands extraordinary effort. Narayana Murthy framed his argument as a moral appeal to nation-building, recalling the post-war reconstruction of countries like Japan and Germany. The underlying belief is that “hard work precedes prosperity.”

Similarly, Elon Musk’s defence of extreme work hours in his companies stems from a mission-driven worldview. For Musk, innovation—whether in electric vehicles or space exploration—requires exceptional commitment. His oft-quoted assertion that “nobody ever changed the world on 40 hours a week” reflects the idea that transformative outcomes demand personal sacrifice.

Critics challenge the glorification of long hours on both empirical and ethical grounds. Studies across countries consistently show that productivity per hour declines sharply beyond a threshold, often around 45–50 hours per week. Beyond this point, fatigue reduces efficiency, creativity, and decision-making quality. Thus, long hours may signal inefficiency rather than dedication.

More importantly, the debate brings mental health to the forefront. In an era marked by anxiety, burnout, and depression, excessive work hours are seen as socially unsustainable. Critics argue that celebrating overwork normalises exploitative work cultures, particularly in economies with weak labour protections.

GenZ and Work:

Younger workers increasingly prioritise work-life balance, flexibility, and mental well-being. For them, productivity is measured not by hours logged but by outcomes achieved.

A 2024 Unstop survey showed that 47% of Gen Z prioritise work-life balance above salary or job title, and prefer jobs that allow hybrid working, meaningful tasks, and mental well-being support. The same survey revealed that young employees are more willing than any previous generation to quit a job that feels draining, even within a year.

But, we are not here to debate, who is right or who is wrong …..

We need to understand that, GenZ has this ability because their pervious generation sacrificed a lot. So comparing choices of GenZ with their previous generation is wrong on so many levels.

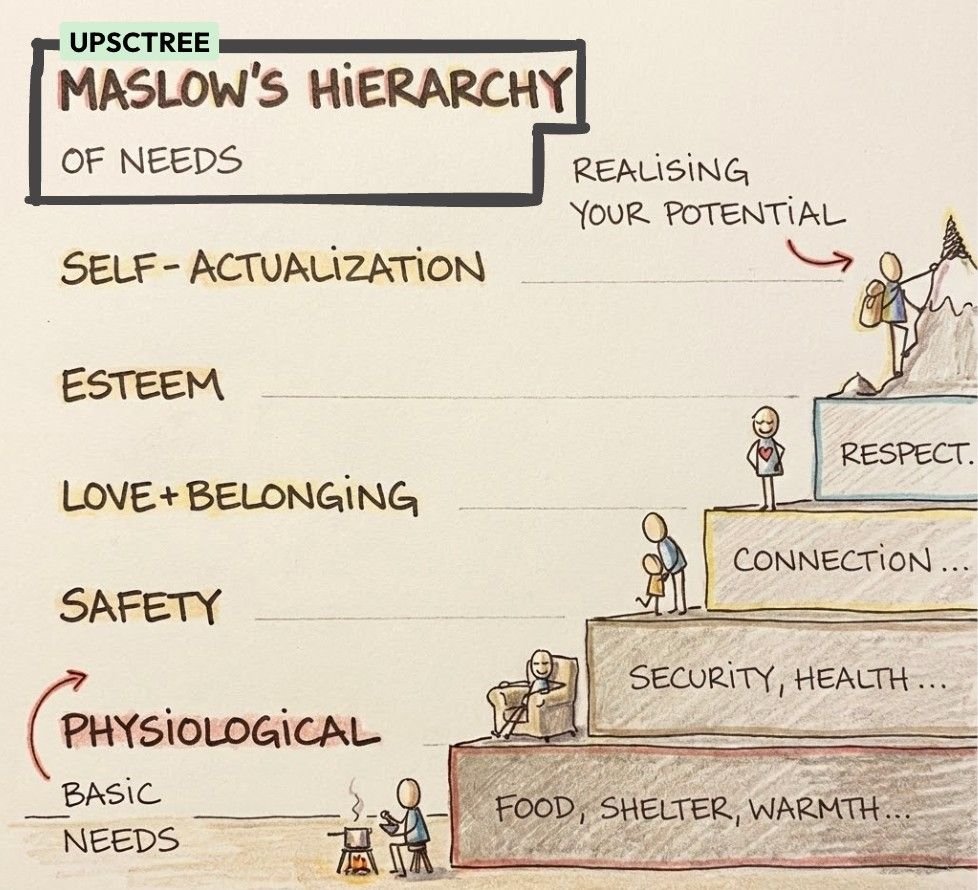

This shift in attitude can be very well explained by a theory from Psychology : Known as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

What is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

Maslow argued that human motivation progresses through stages—from physiological needs and safety, to belonging, esteem, and finally self-actualisation. When survival and security dominate, work becomes a necessity. When these needs are largely met, work becomes a means of self-expression and fulfilment.

For much of India’s post-independence history, employment was about survival and stability. Long hours were not a choice but a compulsion. Today, many young Indians enter the workforce with basic needs already secured. As a result, their aspirations naturally shift towards autonomy, purpose, and well-being.

For much of India’s post-independence history, employment was about survival and stability. Long hours were not a choice but a compulsion. Today, many young Indians enter the workforce with basic needs already secured. As a result, their aspirations naturally shift towards autonomy, purpose, and well-being.

As Maslow famously noted, “What a person can be, they must be.”

Gen Z’s approach to work reflects this transition from survival-driven labour to meaning-driven engagement.

This does not render calls for hard work irrelevant. Nation-building, innovation, and crisis moments will always demand extraordinary effort from some sections of society. But it does suggest that a single work ethic cannot be imposed across generations, sectors, or stages of development. The mistake lies in universalising exceptional conditions into everyday norms.

Ultimately, the debate on work culture must move beyond glorifying exhaustion or romanticising leisure. As societies progress, the goal should not be to work endlessly, but to work intelligently and sustainably. In redefining the culture of work, the task is not to reject the past—but to evolve from it.

Recent Posts

- In the Large States category (overall), Chhattisgarh ranks 1st, followed by Odisha and Telangana, whereas, towards the bottom are Maharashtra at 16th, Assam at 17th and Gujarat at 18th. Gujarat is one State that has seen startling performance ranking 5th in the PAI 2021 Index outperforming traditionally good performing States like Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka, but ranks last in terms of Delta

- In the Small States category (overall), Nagaland tops, followed by Mizoram and Tripura. Towards the tail end of the overall Delta ranking is Uttarakhand (9th), Arunachal Pradesh (10th) and Meghalaya (11th). Nagaland despite being a poor performer in the PAI 2021 Index has come out to be the top performer in Delta, similarly, Mizoram’s performance in Delta is also reflected in it’s ranking in the PAI 2021 Index

- In terms of Equity, in the Large States category, Chhattisgarh has the best Delta rate on Equity indicators, this is also reflected in the performance of Chhattisgarh in the Equity Pillar where it ranks 4th. Following Chhattisgarh is Odisha ranking 2nd in Delta-Equity ranking, but ranks 17th in the Equity Pillar of PAI 2021. Telangana ranks 3rd in Delta-Equity ranking even though it is not a top performer in this Pillar in the overall PAI 2021 Index. Jharkhand (16th), Uttar Pradesh (17th) and Assam (18th) rank at the bottom with Uttar Pradesh’s performance in line with the PAI 2021 Index

- Odisha and Nagaland have shown the best year-on-year improvement under 12 Key Development indicators.

- In the 60:40 division States, the top three performers are Kerala, Goa and Tamil Nadu and, the bottom three performers are Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand and Bihar.

- In the 90:10 division States, the top three performers were Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and Mizoram; and, the bottom three performers are Manipur, Assam and Meghalaya.

- Among the 60:40 division States, Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh are the top three performers and Tamil Nadu, Telangana and Delhi appear as the bottom three performers.

- Among the 90:10 division States, the top three performers are Manipur, Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland; and, the bottom three performers are Jammu and Kashmir, Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh

- Among the 60:40 division States, Goa, West Bengal and Delhi appear as the top three performers and Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Bihar appear as the bottom three performers.

- Among the 90:10 division States, Mizoram, Himachal Pradesh and Tripura were the top three performers and Jammu & Kashmir, Nagaland and Arunachal Pradesh were the bottom three performers

- West Bengal, Bihar and Tamil Nadu were the top three States amongst the 60:40 division States; while Haryana, Punjab and Rajasthan appeared as the bottom three performers

- In the case of 90:10 division States, Mizoram, Assam and Tripura were the top three performers and Nagaland, Jammu & Kashmir and Uttarakhand featured as the bottom three

- Among the 60:40 division States, the top three performers are Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Orissa and the bottom three performers are Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and Goa

- In the 90:10 division States, the top three performers are Mizoram, Sikkim and Nagaland and the bottom three performers are Manipur and Assam

In a diverse country like India, where each State is socially, culturally, economically, and politically distinct, measuring Governance becomes increasingly tricky. The Public Affairs Index (PAI 2021) is a scientifically rigorous, data-based framework that measures the quality of governance at the Sub-national level and ranks the States and Union Territories (UTs) of India on a Composite Index (CI).

States are classified into two categories – Large and Small – using population as the criteria.

In PAI 2021, PAC defined three significant pillars that embody Governance – Growth, Equity, and Sustainability. Each of the three Pillars is circumscribed by five governance praxis Themes.

The themes include – Voice and Accountability, Government Effectiveness, Rule of Law, Regulatory Quality and Control of Corruption.

At the bottom of the pyramid, 43 component indicators are mapped to 14 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that are relevant to the States and UTs.

This forms the foundation of the conceptual framework of PAI 2021. The choice of the 43 indicators that go into the calculation of the CI were dictated by the objective of uncovering the complexity and multidimensional character of development governance

The Equity Principle

The Equity Pillar of the PAI 2021 Index analyses the inclusiveness impact at the Sub-national level in the country; inclusiveness in terms of the welfare of a society that depends primarily on establishing that all people feel that they have a say in the governance and are not excluded from the mainstream policy framework.

This requires all individuals and communities, but particularly the most vulnerable, to have an opportunity to improve or maintain their wellbeing. This chapter of PAI 2021 reflects the performance of States and UTs during the pandemic and questions the governance infrastructure in the country, analysing the effectiveness of schemes and the general livelihood of the people in terms of Equity.

Growth and its Discontents

Growth in its multidimensional form encompasses the essence of access to and the availability and optimal utilisation of resources. By resources, PAI 2021 refer to human resources, infrastructure and the budgetary allocations. Capacity building of an economy cannot take place if all the key players of growth do not drive development. The multiplier effects of better health care, improved educational outcomes, increased capital accumulation and lower unemployment levels contribute magnificently in the growth and development of the States.

The Pursuit Of Sustainability

The Sustainability Pillar analyses the access to and usage of resources that has an impact on environment, economy and humankind. The Pillar subsumes two themes and uses seven indicators to measure the effectiveness of government efforts with regards to Sustainability.

The Curious Case Of The Delta

The Delta Analysis presents the results on the State performance on year-on-year improvement. The rankings are measured as the Delta value over the last five to 10 years of data available for 12 Key Development Indicators (KDI). In PAI 2021, 12 indicators across the three Pillars of Equity (five indicators), Growth (five indicators) and Sustainability (two indicators). These KDIs are the outcome indicators crucial to assess Human Development. The Performance in the Delta Analysis is then compared to the Overall PAI 2021 Index.

Key Findings:-

In the Scheme of Things

The Scheme Analysis adds an additional dimension to ranking of the States on their governance. It attempts to complement the Governance Model by trying to understand the developmental activities undertaken by State Governments in the form of schemes. It also tries to understand whether better performance of States in schemes reflect in better governance.

The Centrally Sponsored schemes that were analysed are National Health Mission (NHM), Umbrella Integrated Child Development Services scheme (ICDS), Mahatma Gandh National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS), Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SmSA) and MidDay Meal Scheme (MDMS).

National Health Mission (NHM)

INTEGRATED CHILD DEVELOPMENT SERVICES (ICDS)

MID- DAY MEAL SCHEME (MDMS)

SAMAGRA SHIKSHA ABHIYAN (SMSA)

MAHATMA GANDHI NATIONAL RURAL EMPLOYMENT GUARANTEE SCHEME (MGNREGS)