Syllabus Connect:- GS III (Energy)

Context:-

At the beginning of the new millennium, amid growing awareness of the link between energy-related greenhouse gas emissions and climate change, the notion of a ‘nuclear renaissance’ became popular. Scientists and policy makers identified low carbon nuclear power as a potential protagonist in the transition to clean energy.

However, the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), on 11 March 2011 dealt a blow to plans for swiftly scaling up nuclear power to address not only climate change, but also energy poverty and economic development.

As the global community turned its attention to strengthening nuclear safety, several countries opted to phase out nuclear power.

Following efforts to strengthen nuclear safety and with global warming becoming ever more apparent, nuclear power is regaining a place in global debates as a climate-friendly energy option. That is due to its vital attributes: zero emissions during operation, 24/7 availability, a small land footprint and the versatility to decarbonize ‘hard-to-abate’ sectors in industry and transportation.

But even as technology-neutral organizations such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Energy Agency (IEA) recognize nuclear power’s ability to address major global challenges, the extent to which this clean, reliable and sustainable source of energy will achieve its full potential remains uncertain.

The Fukushima Daiichi accident and public acceptance in some countries continue to cast a shadow over nuclear power’s prospects. Furthermore, in some major markets, nuclear power lacks a favourable policy and financing framework that recognize its contributions to climate change mitigation and sustainable development.

Without such a framework, nuclear power will struggle to deliver on its full potential, even as the world remains as dependent on fossil fuels as it was three decades ago.

Impact on electricity generation

The biggest immediate blow to nuclear electricity generation came in Japan. With public confidence in nuclear power at record low levels following the accident, authorities suspended operations at 46 of the country’s 50 operational power reactors.

Nuclear energy, a strategic priority since the 1960s, supplying almost a third of Japan’s electricity, was suddenly shelved. In 2019, nuclear power provided only 7.5% of Japan’s electricity. Just nine nuclear power reactors have resumed operation.

Meanwhile, public and government opinion turned against nuclear power in some other countries as well.

Germany, less than three months after the accident, decided to phase out nuclear power entirely by 2022. All but six of the country’s 17 power reactors have since been permanently shut down.

Nuclear power produced about 12% of the country’s electricity in 2019 compared with around 25% before the accident at Fukushima Daiichi, while coal-fired plants remained the largest source of electricity, according to the IEA.

Elsewhere, Belgium confirmed plans to exit nuclear power by 2025.

In Italy, a government-backed plan to bring back nuclear power, shuttered since 1990, fizzled.

And countries such as Spain and Switzerland decided not to build new nuclear plants.

Between 2011 and 2020, some 48 GWe of nuclear capacity was lost globally as a total of 65 reactors were either shut down or did not have their operational lifetimes extended.

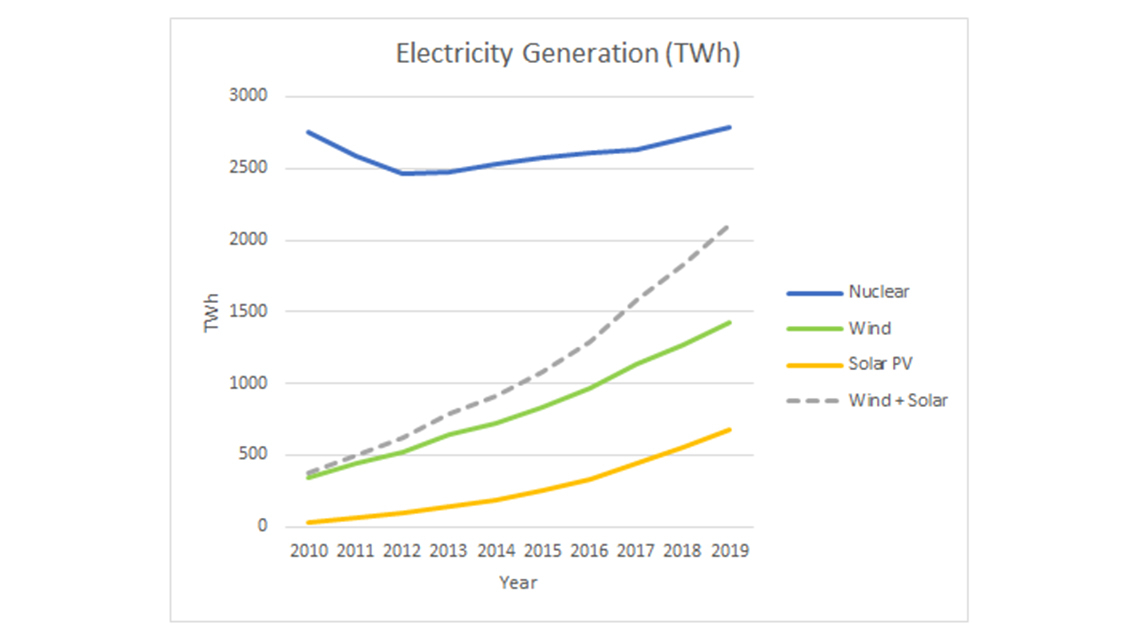

The immediate effect was a decline in global nuclear electricity generation through 2012. At the same time, efforts to deploy other low carbon sources, such as variable wind and solar, intensified as countries looked for new ways to address the climate crisis.

Still, nuclear energy remained the world’s second largest source of low carbon electricity after hydro, providing at the time about 40% of all low carbon power.

Rebuilding confidence

The road back for nuclear power was built on actions taken at the national and international levels to share factual information on the real impact of the Fukushima Daiichi accident and further strengthen nuclear safety, combined with ongoing innovations in reactor design and performance and the long-term operation (LTO) of existing plants.

While newbuild projects in some liberalized markets faced cost and schedule overruns, several countries have made significant progress on the deployment of large scale advanced reactors, including in Belarus, China, the Republic of Korea, Russia and the United Arab Emirates. Russia’s deployment in 2016 of the BN-800 fast reactor, a technology that minimizes waste, underscored the potential for nuclear power’s long-term sustainability.

Meanwhile, efforts accelerated in the development of small modular reactors (SMRs), including the deployment of the first SMRs. Today, SMRs are among the most promising emerging nuclear energy technologies. In comparison to existing reactors, proposed SMR designs generally are simpler and rely more extensively on inherent as well as passive safety features.

They are likely to require lower up-front costs and offer greater flexibility for smaller grid, and integration with renewables and non-electric applications such as hydrogen production and water desalination. Innovative designs will also generate less waste or even run on recycled spent fuel.

Five years after the Fukushima Daiichi accident, as the Paris Agreement entered into force, an increasing number of countries were looking to nuclear power as a means not only to address climate change, but to improve energy security, reduce the impact of volatile fuel prices and make their economies more competitive.

Around 30 countries are working with the IAEA to explore the introduction of nuclear power for the first time.

Bangladesh and Turkey are building their first reactors while Belarus and the UAE started generating nuclear electricity last year, demonstrating the important role that newcomer countries will play in the future of nuclear power.

Nuclear energy’s share of global electricity production also ticked up slightly in 2019, to 10.4%, while generating almost one third of the world’s low carbon power. And in 2020, during the pandemic lockdowns, nuclear power played an important part in providing secure, flexible and stable generation in markets characterized by significant drops in electricity demand and large shares of variable generation

Over the last decade, the centre of nuclear power expansion has shifted to Asia, which accounts for more than two thirds of all reactors under construction. In total, 59 GWe in capacity has been added between 2011 and 2020, including 37 GWe in China alone.

Momentum has also begun to build behind the idea that nuclear power has a key role to play in climate change mitigation as well as sustainable development. When the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were unveiled in 2015, it was clear that nuclear power could contribute to many of them, including economic development, energy access and climate change.

In its 2018 Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5° C, the IPCC’s model pathways showed that nuclear power will need to make a major contribution to keeping the average global temperature increase (relative to pre-industrial times) under this key threshold. In 2019, an IEA report explained how the transition to net-zero emissions by 2050 will be more difficult and expensive without nuclear energy.

The road ahead

Nuclear energy can help slash emissions beyond the electricity sector as well as address electricity consumption growth, air quality concerns, energy supply security and the price volatility of other fuels. Yet its prospects in some countries remain clouded by policy uncertainty, which adds to the cost of financing this capital-intensive technology.

In its latest annual projections published in September 2020, the IAEA said nuclear generation capacity could almost double by 2050 or decline to slightly below current levels.

According to the report, immediate and concerted action is required to reach the high case scenario. Commitments made under the Paris Agreement and other initiatives could support nuclear power development, but that would require the establishment of energy policies and market designs to facilitate investments in dispatchable, low carbon technologies.

One immediate challenge is the age of the reactor fleet. More than two thirds of operational reactors are over 30 years old and will either be retired in the coming decades or have their lifetimes extended. The anticipated shutdowns of a combined 13 reactors in Germany and Belgium by 2022 and 2025 respectively represent some 14 GWe of lost capacity. The fate of existing reactors in Europe, Japan and the US also remains unclear.

The challenge ahead is to build a safe bridge between ageing reactors and the deployment of advanced technologies. Existing rectors must maintain safety and reliability while staying economically competitive. Advanced reactors under development must be backed up by a proof of concept to successfully clear regulatory hurdles.

Beyond electricity

Global electricity needs, meanwhile, are poised to rise in the decades to come and in key energy scenarios that achieve stringent mitigation targets, a significant role for nuclear power is envisaged. That’s because decarbonizing electricity production through greater use of nuclear power, hydro, wind and solar is only the first step. Clean energy is also needed by sectors such as industry, transport and buildings if the world is to achieve net zero by 2050.

Nuclear power can be used to produce low carbon hydrogen at a competitive cost. Low carbon hydrogen is a key future option for the transport sector, where emissions have tripled since 1970.

While nuclear power’s role on climate change and sustainable development has become better known since the Fukushima Daiichi accident, public acceptance and policy uncertainty still constitute hurdles to the nuclear renaissance once envisaged—but it’s role for future is undeniable.