Written by : Umakant Sir (ex-Civil Servant & Mentor)

GenZ does not want to work endlessly, because their parents and grandparents did. And there is nothing wrong about it.

GenZ prefers meaningful work rather than “just hard work”.

The Debate of Work:

The question of how much one should work has re-emerged as a contentious public debate in recent times. Statements by business leaders such as Elon Musk, who advocates 80–100 hour workweeks, and N.R. Narayana Murthy, who called for a 70-hour workweek for India’s youth, have reignited discussions on productivity, national growth, and personal well-being.

At its core, the debate reflects a deeper conflict between industrial-era notions of sacrifice and post-industrial concerns for sustainability, dignity, and mental health.

Proponents of longer working hours argue from the standpoint of economic urgency and competitive pressure. For developing economies like India, they contend, rapid growth demands extraordinary effort. Narayana Murthy framed his argument as a moral appeal to nation-building, recalling the post-war reconstruction of countries like Japan and Germany. The underlying belief is that “hard work precedes prosperity.”

Similarly, Elon Musk’s defence of extreme work hours in his companies stems from a mission-driven worldview. For Musk, innovation—whether in electric vehicles or space exploration—requires exceptional commitment. His oft-quoted assertion that “nobody ever changed the world on 40 hours a week” reflects the idea that transformative outcomes demand personal sacrifice.

Critics challenge the glorification of long hours on both empirical and ethical grounds. Studies across countries consistently show that productivity per hour declines sharply beyond a threshold, often around 45–50 hours per week. Beyond this point, fatigue reduces efficiency, creativity, and decision-making quality. Thus, long hours may signal inefficiency rather than dedication.

More importantly, the debate brings mental health to the forefront. In an era marked by anxiety, burnout, and depression, excessive work hours are seen as socially unsustainable. Critics argue that celebrating overwork normalises exploitative work cultures, particularly in economies with weak labour protections.

GenZ and Work:

Younger workers increasingly prioritise work-life balance, flexibility, and mental well-being. For them, productivity is measured not by hours logged but by outcomes achieved.

A 2024 Unstop survey showed that 47% of Gen Z prioritise work-life balance above salary or job title, and prefer jobs that allow hybrid working, meaningful tasks, and mental well-being support. The same survey revealed that young employees are more willing than any previous generation to quit a job that feels draining, even within a year.

But, we are not here to debate, who is right or who is wrong …..

We need to understand that, GenZ has this ability because their pervious generation sacrificed a lot. So comparing choices of GenZ with their previous generation is wrong on so many levels.

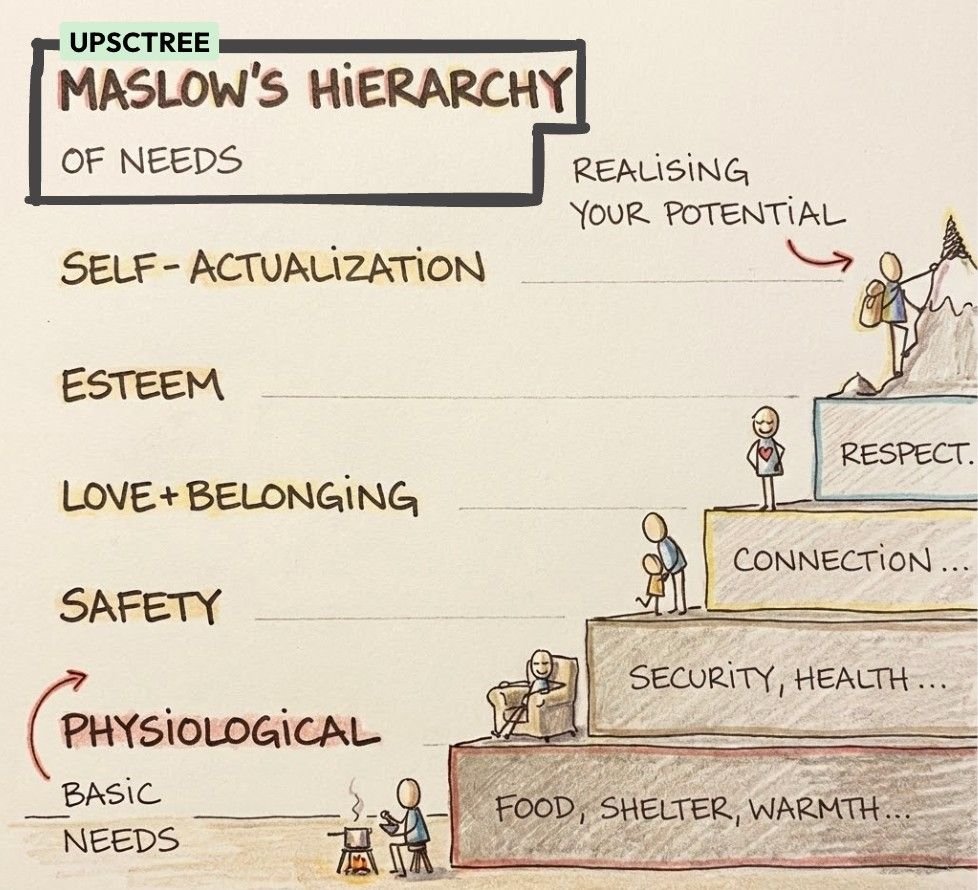

This shift in attitude can be very well explained by a theory from Psychology : Known as Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

What is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs:

Maslow argued that human motivation progresses through stages—from physiological needs and safety, to belonging, esteem, and finally self-actualisation. When survival and security dominate, work becomes a necessity. When these needs are largely met, work becomes a means of self-expression and fulfilment.

For much of India’s post-independence history, employment was about survival and stability. Long hours were not a choice but a compulsion. Today, many young Indians enter the workforce with basic needs already secured. As a result, their aspirations naturally shift towards autonomy, purpose, and well-being.

For much of India’s post-independence history, employment was about survival and stability. Long hours were not a choice but a compulsion. Today, many young Indians enter the workforce with basic needs already secured. As a result, their aspirations naturally shift towards autonomy, purpose, and well-being.

As Maslow famously noted, “What a person can be, they must be.”

Gen Z’s approach to work reflects this transition from survival-driven labour to meaning-driven engagement.

This does not render calls for hard work irrelevant. Nation-building, innovation, and crisis moments will always demand extraordinary effort from some sections of society. But it does suggest that a single work ethic cannot be imposed across generations, sectors, or stages of development. The mistake lies in universalising exceptional conditions into everyday norms.

Ultimately, the debate on work culture must move beyond glorifying exhaustion or romanticising leisure. As societies progress, the goal should not be to work endlessly, but to work intelligently and sustainably. In redefining the culture of work, the task is not to reject the past—but to evolve from it.