Critical minerals are considered to be the ‘new oil’, with the potential to drive the high-technology industrial revolution. However, the concentration of critical mineral supply chains along the downstream, middle, and upstream segments in specific states, such as China, has created security challenges for other countries; this is true for the Quad members.

Consequently, countries are developing policies and strategies to create a resilient supply chain. The European Union (EU) and countries such as Canada, India, Australia, and South Korea have acknowledged the importance of critical minerals and have released either a strategy or a list of critical minerals.

Currently, the global critical mineral supply chain is concentrated among a few key players along the upstream segment, including China, Australia, and the United States (US), and regions like Latin America and Central Asia.

China controls the midstream and downstream segments.

Much of the competition is concentrated in the Indo-Pacific region. In this context, the Quad members’ push to secure the critical mineral supply chain is driven by economic growth targets and the pursuit of development and regional influence.

China’s Dominance and Weaponization of Critical Minerals:

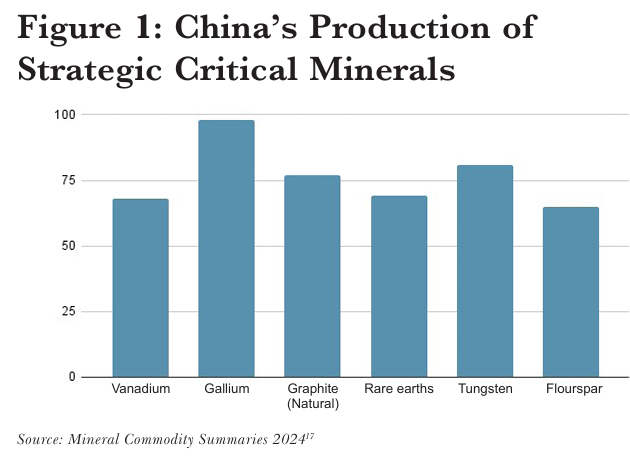

China currently dominates the supply chain for critical minerals, including rare-earth elements (REEs) such as neodymium and dysprosium, capturing 60 percent of global REE production and almost 90 percent of worldwide processing and refining capacity

China’s domination of the critical minerals supply chain presents risks for adversaries.

In 2010, Beijing began weaponising the critical minerals supply chain by halting the export of REEs to Japan.

In 2023, Beijing began using trade weaponisation as a foreign policy tool, restricting the global export of critical minerals such as germanium and gallium.

Recognising the risk associated with the high dependence on China for strategic minerals, a number of countries began de-risking from China after the pandemic. However, the extent of de-risking differed across countries, depending on their requirements and relations with Beijing.

As the great-power rivalry intensifies, states are becoming more anxious about their dependence on China, particularly countries from groups like the Quad and AUKUS—i.e., India, Australia, Japan, the United Kingdom (UK), and the US—which have adversarial relations with Beijing.

The dependence on China is expected to increase if proper steps are not taken at the appropriate speed and scale. Existing initiatives are uneconomical and unsustainable.

Current projections indicate that the demand for lithium and REEs will experience a sharp increase between 2030 and 2050.This demand is expected to be fulfilled by China for the next decade.

The current supply of lithium is estimated to be able to meet only 50 percent of the demand by 2035. Similarly, the demand of REEs is estimated to increase by three to seven times by 2040 per current levels, with China continuing to dominate 55 percent in mining and 78 percent in refining, respectively.

This projection highlights severe challenges for Quad members in the long term, especially as geopolitical competition with China escalates in all domains.

The Quad and Critical Minerals:

The Quad members have their respective strengths in critical minerals:

Australia is a resource-rich state with critical minerals reserves; the US has the technological capability for mining; Japan has the capital and extensive experience in extracting and processing; and India has rich reserves of unexploited minerals and a growing consumer market. These capabilities, if combined, can produce positive results for the countries themselves as well as for the Indo-Pacific region.

Australia: A Resource Reserve State

Australia aims to position itself as the source of raw minerals for the world.

In 2023, Australia released its Critical Minerals Strategy 2023-2030, which highlights its political, economic, and strategic priorities to attract more sustainable financial investments into the critical minerals sectors.

Australia aims to become a vital player in the upstream and downstream segments of the supply chain, including in mining and processing, leveraging its second position only to China in “exploration investment, reserves, and capital expenditure”.

To fulfil this objective, Australia has established relations with 26 countries globally, including seven—the US, EU, UK, Japan, South Korea, Canada, and India—who are also considered supply chain partners.

India: Manufacturing Hub:

Critical minerals are essential for India’s national security and development. However, this emphasis became noticeable in 2019.

India did not participate in global discussions regarding the dependence on China for critical minerals, following Beijing retaliating against Japan in 2010.

New Delhi’s quest to secure its critical mineral supply chain began after the COVID-19 pandemic and has since accelerated. This was acknowledged by Prahlad Joshi, Former Indian Minister of Coal and Mines, who emphasised that “this is the first time our country has identified the comprehensive list of critical minerals taking into account the needs of sectors like defence, agriculture, energy, pharmaceutical, telecom etc.”

This was the result of disruptions in the raw material supply chain and its increased dependence on other countries, including China, for minerals such as lithium and lithium-ion imports.

However, the India-China border conflict was one of the crucial factors in reaffirming India’s strategic concerns regarding China, including its dependence for critical minerals.

Recently, Indian Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, while addressing a strategic community gathering, emphasised India’s critical mineral vulnerability without naming China, saying, “While scramble for resources for economic reasons has had a long history, their weaponisation by some nations for strategic reasons is a comparatively new phenomenon. These tendencies are not conducive for the global good”

In 2023, the India released its first list, which comprised 30 critical minerals.

To fulfil the new vision, India began focusing on unexploited minerals domestically, based on two pillars: making the mining process for critical minerals easy and business-friendly and fostering international cooperation with resource-rich countries.

To facilitate the first pillar, in 2023, India introduced the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulations) Amendment (MMDR) bill to liberalise the mining sector and passed the bill through parliament.

For instance, the government delisted six minerals from the atomic list, facilitating mining by private players and allowing the government to auction.

Subsequently, the government announced the royalty rates for 24 critical minerals, as mentioned in Part D of the first schedule of the MMDR Act.

India’s Import Dependence on Third Countries for Critical Minerals

India has now adopted a whole-system approach to securing critical minerals supply chains, focusing on coordinating with stakeholders from industry, academia, think tanks, and public and private sectors to bring together and leverage the capacities of different ministries and private companies to promote critical mineral mining, extraction, and processing.

This vision was first partially stated in National Mineral Policy (NMP) 2019, which stressed a more effective, meaningful, and implementable policy that brings transparency, better regulation and enforcement, balanced social and economic growth, and sustainable mining practices.

India has also joined global initiatives on critical minerals, such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework and the Mineral Security Partnership, to further the vision in line with the NMP 2019, which states that “particular attention will be given to the prospecting and exploration of minerals in which the country has a poor resource-cum-reserve base despite having the geological potential for large resources.”

The progress achieved till date is evident in the increased exploration projects approved in India since 2019, However, responses following three tranches of auctions among private players has been lacklustre.

For international collaborations on critical minerals, the Indian government created a public-sector enterprise called Khanjij Bidesh Private Ltd. (KABIL) in 2019, which aims to identify and acquire overseas mineral resources such as lithium, cobalt, and other minerals.

So far, KABIL has finalised agreements with Australia and Argentina and is finalising a deal with Chile. Additionally, India is reported to be in talks with Sri Lanka for acquiring graphite mines in the island state.

United States: Technology Leader

Critical minerals form an essential part of the US Grand Strategy, which aims to maintain its supremacy in the digital era, where it faces strict competition from China.

Mineral resources can also help the US secure its future through green energy transition and advanced defence manufacturing, which will scale according to the increasing demand for critical minerals.

Therefore, unlike other countries that look at the critical mineral supply chain issue from the perspective of economic opportunities, the US seeks to eliminate existing strategic impediments that may threaten its position as the global technological leader, which necessitates its control over the supply chain.

Accordingly, the US strategy is based on four pillars: “Diversifying supplies of critical minerals and materials; Developing alternatives to critical minerals and materials; Improving materials and manufacturing efficiency; and Investing in circular-economy approaches.”

In 2022, the United States Geographical Survey (USGS) released a list of 50 minerals categorised as critical. The Department of Energy also released their critical mineral lists in 2023.

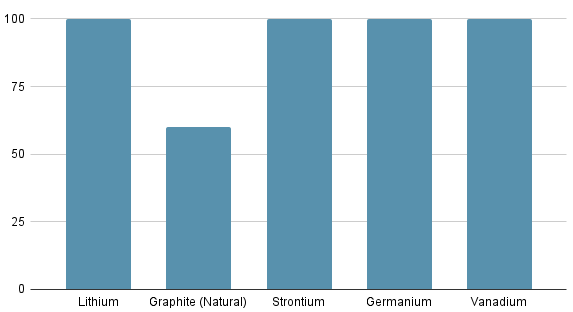

Currently, the US is entirely dependent on third countries (including China) for 12 critical minerals and 50 percent reliant for another 29 critical minerals.

With targets such as reducing greenhouse gases by 2030, achieving net zero by 2050, and carbon-pollution-free electricity by 2035, the US is under increasing pressure to fast-track all its initiatives to meet domestic needs and manufacturing objectives.

To manage its domestic priorities and international commitments and maintain its position as the technology leader, Washington has introduced initiatives such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and other methods such as tariffs, aimed at attracting domestic investment in critical minerals supply chains across all segments and simultaneously limiting Chinese access to the US market.

Among the Quad member states, the US is the only country that has adopted a strong stance regarding critical minerals. The tariffs implemented under US President Joe Biden on critical mineral imports is an example of the extent to which the administration is willing to push against Chinese control over the supply chain.

The US has introduced new, increased tariffs, from 0-25 percent on some critical minerals and 25 percent on graphite and permanent magnets.

The tariffs target the whole supply chain of critical minerals, from mining to processing upstream, midstream, and downstream. Tariffs have also been introduced for EVs, battery parts, lithium-ion EVs, and non-EV batteries.

These steps are part of larger efforts that began in the Biden administration’s second year through the IRA, which restricted EV imports from a “foreign entity of concern”, mainly aimed at stopping the inflow of China-made EVs and providing incentives to promote domestic EV production.

Japan: Capital Provider and Facilitator:

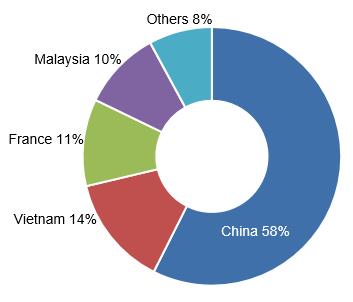

As a resource-scarce country and export-dependent economy, Japan does not hold any major strategic reserves of minerals and depends on third countries, including China, for its critical mineral consumption; for instance, 60 percent of its rare-earth imports come from China.

The consequences of critical mineral supply chain vulnerability were first felt in Japan, when China stopped the export of rare earth elements to the country in 2010.

Since then, Japan has made a consistent effort to de-risk its critical mineral supply chain by focusing on five main pillars.

In 2020, Japan released its International Resource Strategy to secure a stable supply of mineral resources; the strategy focused on stockpiling strategic minerals, including REEs, at 30 days for some metals, 60 days for sensitive metals, and 180 days for highly geopolitically risky metals.

Japan’s dependence of other countries:

The Quad and Critical Minerals: Potential and Opportunities

The Quad and Critical Minerals: Potential and Opportunities

Since 2021, the Quad has taken steps towards fostering strong cooperation on critical minerals. The private sector-led Quad Investors Network (QUIN) was launched during the second Quad Leaders’ Summit in 2022 and has since worked towards identifying areas of cooperation on the critical mineral supply chain.

Currently, a few Quad members have exclusive critical mineral agreements with each other or are negotiating separate agreements with other members .

In 2023, the US signed an agreement with Japan on critical minerals. In the same year, the US and Australia established a task force focused on “identified areas in which the U.S. and Australian governments can take joint action to increase investment in critical minerals mining and processing projects.”

India has a critical mineral agreement with only Australia and none with the other Quad members.

The Quad has the political will and strategic vision to invest in developing a resilient and secure critical mineral supply chain. Currently, however, the Quad needs an overarching framework on critical minerals.

Quad can bring together Indo-Pacific multilateral initiatives operating in the domain, including the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and other minilaterals, most of which are being led by the US.

As the demand for green technologies increases, more countries are exploring options to invest in renewable energy sources, which are highly dependent on critical minerals.

For instance, India lacks the technological expertise and skills to benefit from its critical mineral reserves.

Australia has rich sources of critical minerals, including lithium, uranium, and heavy REEs like dysprosium, which can satisfy the growing demand for critical minerals in the Indo-Pacific region.

For its part, India has rich resources of light REEs, such as neodymium and praseodymium, as well as other minerals like iron ore and manganese.

The Quad’s rationale for collaboration should be two fold: first, to create a resilient supply chain to protect its interests and offer alternatives to the region, and second, to ensure that the supply chain is not concentrated in one country.

The latter is necessary as the domination of one player enables market manipulation or economic coercion, further dampening investor interests, affecting government policies, and requiring regular executive intervention.

The Quad must ensure that global markets are not manipulated and can handle supply chain vulnerabilities without external interventions. The grouping needs to align its critical mineral initiatives with the broader Indo-Pacific region to address these issues through minilateral and multilateral efforts such as the IPEF and MSP.

For example, the Quad can identify common minerals for all countries and work on a collaborative mechanism to secure the supply chains for those minerals. Its role should be to diversify the supply chain of critical minerals to provide financial stability to like-minded countries in the region.

Challenges:

Although the Quad members have taken steps to strengthen cooperation in critical minerals, challenges remain. Attempts by Quad members like Australia and the US to restrict domestic Chinese funding in mining have backfired, requiring many projects to be revised.

At the same time, other projects like BHP Group’s Nickel business have become economically unviable. The flood of Chinese minerals into the market has made businesses unviable.

The following paragraphs outline the factors that have contributed to the Quad members’ weakening position vis-a-vis China:

1) Lack of economic realism:

Quad members’ attempts to emerge as alternatives to China have not succeeded due to ill-informed expectations. For example, despite Australia’s efforts to diversify its consumers, China remains the largest market for Australian and Australia-produced critical minerals, including rare-earths, amounting to US$100 billion.

For example, nickel prices crashed from US$45,000 in March 2022 to US$15,900 in 2023, forcing Western companies like BHP Australia to cease operations.

This was a consequence of Indonesia ramping up production of nickel, with 95 percent of the ferronickel that was produced being exported to China.

2) Lack of understanding of critical mineral supply chain and industry demand:

There is a lack of expertise in next-generation technology, production costs, and transitional material development in the downstream segment of the supply chain, such as in advanced battery materials research and development. Therefore, most of the strategic investments in critical minerals and rare-earths remain removed from reality, which further jeopardises mining investments.

Research on new battery technologies for replacing minerals like lithium and cobalt are not considered in investment decisions, which poses risks for capital investments in the sector. Meanwhile, China has invested billions in new technologies such as semi-solid-state, solid-state, and sodium-ion batteries and is working on sodium-ion cells that have the potential to lower production costs.

3) Policy uncertainty

This remains a challenge for all Quad partners. Unlike the centralised political system in China, Quad democracies have decentralised decision-making at the federal and provincial levels.

For instance, markets and companies cannot be forced to invest in projects that undermine geopolitical and economic rationales.

One example is ESG. The Quad’s prospects in critical mineral mining have not fructified due to its strict emphasis on ESG compliance and lack of intra-grouping agreement.

For instance, India’s approach towards ESG remains underdeveloped, and there is a lack of clarity and convergence with the Western approach towards ESG, even in specific sectors like critical minerals mining.

4) Risk of a zero-sum game

Establishing an alternative, resilient, and secure supply chain will have its disadvantages. Beijing views joint efforts such as these to be targeted towards diminishing Chinese hegemony and is reciprocating with critical minerals restrictions and curbs.

These actions risk starting a zero-sum game involving the Quad members, paving the way for a further fragmentation of the supply chain.

Conclusion:

Emerging technologies like EVs, semiconductor chips, batteries, and green technologies will drive the next industrial revolution.

States that have control over the building blocks of these technologies, i.e., critical minerals and their supply chain, will control supply, set standards, and influence prices.

At present, China controls the entire supply chain of minerals, from extracting and processing to value addition.

In the case of third countries, the supply chain becomes intertwined with geopolitics and industrial policy, which poses a threat to states dependent on China for their mineral needs.

Therefore, it is essential for like-minded countries, particularly groups like the Quad, to mobilise resources, capital, and expertise to support an alternative supply chain that is robust, resilient, and trustworthy towards achieving mineral security.