Winter is coming – and it is DEMOGRAPHIC !!!

For most of their existence, hominids lived much like other animals. Over hundreds of thousands of years, their numbers were shaped by natural selection, with high birth rates matched by equally high death rates.

A decisive shift came with the emergence of Homo sapiens. We spread across the Earth, built the first permanent settlements, and learned to domesticate plants and animals. By the beginning of the Common Era, the world’s population is estimated to have been around 250 million.

It took nearly 1,600 years for our numbers to double to 500 million, a process further slowed by catastrophes such as the Black Death in the fourteenth century. After this, the pace of growth began to quicken. By 1804, our population reached one billion for the first time, reflecting the transformative effects of industrialisation, improved agriculture, and medical advances.

In 1798, the English economist Thomas Malthus presented his Essay on the principle of population. In it, he popularized the idea of the Malthusian trap (or Malthusian catastrophe), according to which he predicted that the population would continue to grow exponentially, doubling every 25 years, while resources would only grow arithmetically. This decoupling, according to Malthus’ theory, would cause continuous impoverishment of citizens, leading to the extinction of humanity by 1880.

Extinction did not occur in 1880; however, the human population continued to expand at an unusually rapid pace. In 1927, the population reached 2 billion, and in 1975, it reached 4 billion. Gladly, technological advances continued to improve food production, and medicine made it possible to effectively combat diseases that were previously incurable. However, the fear of overpopulation remained latent in society, and many organisations continued to warn of the great threat and its consequences.

The demographic transition:

After analysing demographic changes in several countries following industrialisation, scientists such as Warren Thompson and Adolphe Landry began to propose a series of demographic theories that would eventually be formalised in the 1940s by Frank W. Notestein. This model is known as the theory of demographic transition.

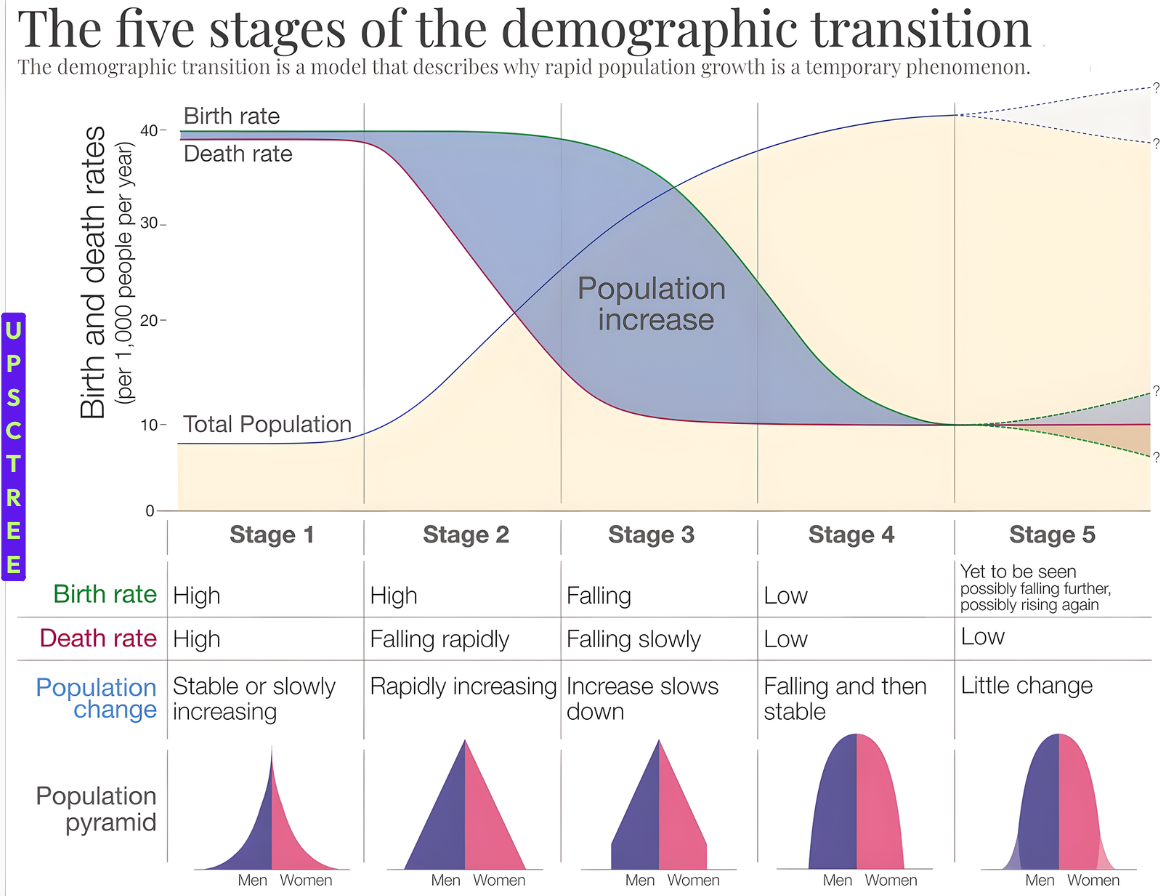

This model is based on a premise that can be verified with historical data: pre-industrial societies had very low growth rates, with very high birth and death rates. With industrialisation, societies moved from this paradigm to one of zero growth, in which both birth and death rates plummeted to record lows. The most interesting part of the model is how this transition occurs. The decline in mortality and birth rates occurs at different rates, allowing natural population growth (more births than deaths) to skyrocket during this period.

This model, which was initially created to explain industrialisation in the 19th and early 20th centuries, proved to be quite effective in modelling demographic changes throughout the 20th century. Industrialising societies experienced excessive growth, while those that had been industrialised for longer gradually stabilised their natural growth, bringing it closer to the equilibrium predicted by Notestein.

However, at the end of the 20th century, something began to happen that the model did not anticipate. There were countries whose natural growth did not remain at zero, but fell below the replacement rate.

The onset of demographic winter:

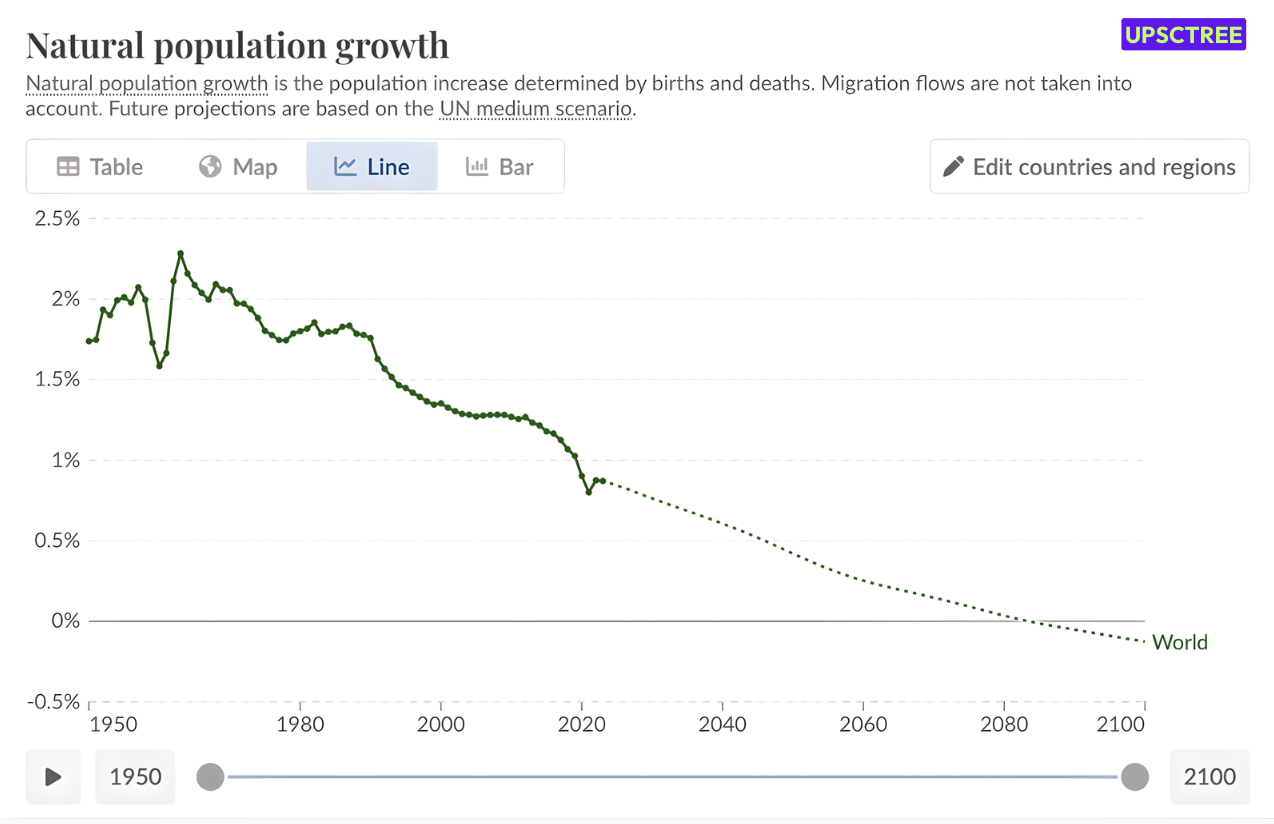

Although there are already many countries, mainly in Europe, with negative natural growth, where deaths outnumber births, there are still more countries where the opposite is true. Africa’s great engine continues to drive growth, but fertility rates continue to decline worldwide, at a much faster pace than expected.

The UN has been revising its global population growth forecasts downwards for several years. In 2017, the estimate was that the global population would peak in 2100, with a total of 11.2 billion inhabitants. A couple of years ago, in 2022, this was revised downwards, with an estimated peak of 10.4 billion in 2084. Global population growth is declining, and zero growth will not be the end point of this demographic trend.

We are already seeing how negative population growth in many countries is being offset by migration flows, but this solution may have significant long-term consequences. Few countries currently function as magnets for migrants, but this number will grow.

China is already losing inhabitants, and fertility rates suggest that this decline will be very pronounced in the coming decades.

It will become increasingly common for countries in demographic decline to start competing for migrants from the few countries with positive natural growth.

From this perspective, demographic winter appears to be a plausible long-term outcome for humanity. While future medical, technological, or social transformations could fundamentally alter current trends, existing evidence makes it difficult to envisage a radically different trajectory.