Scientists say a month of concentrated efforts is all it takes to control mosquitoes responsible for diseases like dengue and chikungunya. But the claim sounds far-fetched at a time when almost the entire country has been reporting these diseases for the past few months .

The country registered 36,110 confirmed cases of dengue and 14,656 cases of chikungunya till September 11. Government data shows dengue has also claimed 70 lives. An alarming number of cases have been reported of another type of fever whose symptoms are similar to chikungunya and dengue. It is being dubbed mystery fever. Unable to understand what causes the fever, government agencies have started screening for Zika, another vector-borne disease, as a precaution. The National Institute of Virology, Pune, has already checked over 300 blood samples for Zika virus, but the samples have tested negative, confirms D T Mourya, director of the institute.

Ask B N Nagpal, scientist at the National Institute of Malaria Research, Delhi, why the country has failed to avert such an outbreak of vector-borne diseases and he says it is because of lack of political will. “Even if existing methods are employed properly, it is possible to control the population of mosquitoes,” says Nagpal. His sentiments were echoed by the National Green Tribunal, which on September 21, reprimanded the Delhi government for its “shameful and shocking” response to the outbreak. The capital has so far registered four dengue deaths.

Shifting places

A fallout of this political apathy has been the failure of the government to adapt to the changing nature of Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is responsible for the diseases plaguing the country.

Normally, the mosquito would breed only in clean stagnant water accumulated in potholes, discarded containers and tyres. Not only has intermittent rains associated with climate change increased breeding places for the mosquito, the vector is also adapting to newer environments. Now there is evidence that it can grow in dirty water, using it as a habitat throughout the year. A study published in the Indian Journal of Medical Research in 2015 shows that Aedes mosquitoes that breed in dirty water are bigger and have longer wing spans. The National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme’s 2016 Urban Vector-Borne Disease Scheme does not consider dirty water as a breeding area. The authors of the 2015 study suggest that the country’s vector control programme should include sewage drains as breeding habitats of dengue vector mosquitoes.

The scheme includes methods such as controlling mosquito breeding sites, use of anti-larval methods with approved larvicides and biological control through larvivorous fishes and biolarvicides. And even these are not being employed properly, which is clear from the current outbreak.

High on research, low on practice

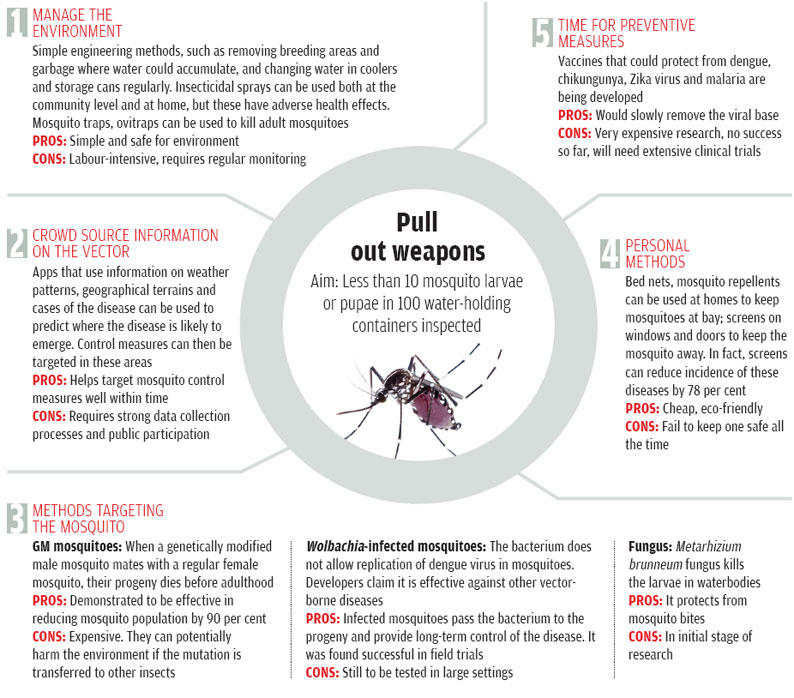

Many innovative methods have been developed in the past few years to fight mosquitoes, but they are still in experimental stages . One way is the use of crowd-sourced data to predict the disease outbreaks in advance. Scientists at Nanyang Technological University (NTU), National University of Singapore (NUS), and the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai (IITB), collaborated to create a web- and mobile-based application for dengue surveillance.

The Mo-Buzz application combines three elements of dengue management—predictive surveillance, civic engagement and health communication. It was first used in Colombo in 2013 through a group of Sri Lanka’s public health inspectors.

The inspectors monitored different areas in the city and fed their reports in the system, which used a pre-loaded algorithm to generate hotspots of infection in real time. “The predictions informed public health inspectors about the areas that needed immediate interventions,” says May O Lwin, professor at NTU and the principal investigator at Mo-Buzz. The application also allows citizens to “report dengue-breeding sites through geo-tagged picture reports”. The application has not been tried in India so far because of funding issues, says Ravi Poovaiah of IITB, who was part of the team that developed the app.

In fact, the lone experiment in India to use crowd sourced data for sensitising people about dengue has been tried by a Mumbai-based agency called Vamanetra Digihealth. The company, set up in April 2014, started an app in Mumbai to detect dengue-breeding spots in the city. “The response from the public was lukewarm primarily because of limited marketing of the product and the underlying campaign,” says Rintu R Patnaik, managing partner, Vamanetra Digihealth.

He adds that the veracity of data is a big issue on crowd-sourcing platforms. “The challenge we faced in running the trial was similar to what the public health teams regularly face—people are generally unwilling to volunteer or allow health workers to find trouble spots that can allow mosquito breeding.” Though the company has stopped developing apps that require crowd sourcing of data, they are still working on modules that rely on government data and open data sets. Patnaik says the behaviour of people can change for the better “through greater media coverage and awareness”.

Researchers across the globe are also actively developing genetically modified (GM) mosquitoes to control vector population. GM mosquitoes are created by injecting the eggs with modified DNA. The male progeny is released to mate with normal mosquitoes and their progeny has a short lifespan.

Oxitec, a British company, has tested GM mosquitoes in Piracicaba, Brazil, and found that it resulted in an 82 per cent decline of the mosquito population in the area in just eight months.

In August last year, the company got a go-ahead from the US Food and Drug Administration to release the GM mosquitoes as part of an investigational field trial in Key Haven in Florida Keys. Residents of Key Haven will soon vote on the trial and the final approval will be given by the Florida Keys Mosquito Control Board. “In India, we have recommended controlled field trials of GM mosquitoes,” says K Gunasekaran, scientist at the Vector Control Research Centre in Puducherry. He says the Department of Science and Technology is in the process of preparing guidelines for conducting trials in India.

The use of GM mosquito, however, is controversial as they have been implicated in the spread of the Zika virus. Zika virus infection began in those areas of Brazil where Oxitec had first released the modified mosquitoes. Even activists in Florida Keys are against the use of these mosquitoes.

Use of Wolbachia bacterium has shown potential in controlling the vector. The bacterium reduces the growth of the disease-causing virus such as dengue, chikungunya and Zika in the body of Aedes aegypti. Both Wolbachia-infected male and female mosquitoes are released into the environment. When they mate with normal mosquitoes, they transfer the bacterium to the progeny. Wolbachia is self-sustaining. “This makes the method cost effective,” says Lewti Hunghanfoo, communications adviser for Eliminate Dengue, international collaboration led by Monash University, Australia.

Some experiments have also shown that when Wolbachia-infected male mosquitoes mate with normal female mosquitoes, they are unable to reproduce. Singapore plans to introduce male Aedes mos quitoes carrying Wolbachia bacteria in three housing estates in October this year. The field trial will continue for six months to assess the impact on the mosquito popu lation. India too plans to use Wolbachia in the next two years.

Preliminary research shows that parasitic fungus Metarhizium brunneum has the potential to control the population of the Aedes mosquito. A study published on July 7, 2016, in PLoS Pathogens demonstrates that the fungus can attack Aedes larvae in a rapid and effective way. Researchers of the study say the approach is safe for humans. The biggest advantage of the fungus is that it grows in freshwater, which is the natural habitat of Aedes mosquito.

There is an Indian invention to combat mosquitoes as well. Hawker is an indigenous mosquito and fly trapper developed by Kerala resident Mathews K Mathew. The device uses biogas to lure mosquitoes and sunlight to kill them. It makes use of the smell from the septic tank to attract the mosquitoes. Once the mosquitoes get trapped, the heat built up inside the device kills them. Mathew says a single Hawker can control mosquito population in 0.4 hectare of land and its surroundings. He initially used Hawker in churches and old age homes and has got a patent for the product. He now plans to start mass-producing the device, which currently sells for Rs 1,500.

He is in talks with officials of the Kochi Municipal Corporation (KMC) because the city has over 260,000 septic tanks. A senior KMC official says, “The device is the most effective fly remedy we have seen so far. It does not produce chemicals or other toxic waste and has a larger operational area with little maintenance cost. We have already proposed to use Hawker widely.”

Experts say the key lies in using a combined effort, which should have both national policies and local innovations.

“All the innovative methods have potential, but it is unlikely that any of them when used alone, will be effective in disease prevention and control. None has been fully validated so it is too early to tell which will be most effective,” says Duane J Gubler, professor emeritus and founding director of Signature Research Program in Emer ging Infectious Disease, Duke-NUS Medical School, Singapore.

The vector Aedes aegypti has spread across the globe and India is infested with it. It is time we used the one-month opportunity to control the population. We have both established and experimental tools. “These are not difficult to implement. What is difficult is to have sustainable commitment by the government and the people,” says Gubler.

Sri Lanka conquers malariaThe last case of malaria was reported in the country in October 2012

The world Health Organization (WHO) declared Sri Lanka malaria-free on September 6, 2016. “Sri Lanka’s achievement is truly remarkable. In the mid-20th century, it was among the most malaria-affected countries, but now it is malaria-free,” says Poonam Khetrapal Singh, WHO regional director. Health officials in Colombo claim that policy and programmatic shifts led to the success. “This is a combination that worked,” says Hemantha Herath, deputy director, Anti-Malaria Campaign. Sri Lanka signed up early for WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme (GMEP) in 1958 which resulted in an immediate decline in reported malaria cases spread by Anopheles mosquito. But malaria cases continued to spike intermittently in the 1960s, 1980s and 1990s. Malaria reached epidemic levels in 1999 with confirmed cases reaching 265,000. This served as a wake-up call for the government. The country first shifted from the single-vector control to an integrated vector-control programme that was applied across the island. A decade later, Sri Lanka added web-based surveillance methods and began working closely with the community to eradicate malaria. By November 2012, there was remarkable progress. The locally reported cases by then stood at zero with the last local case being reported in October 2012. It is about vigilance and follow up, says Herath. In the three years that followed, 95, 49 and 36 cases of malaria were reported, all of them having contracted malaria overseas. Due to a strong web-based surveillance, the campaign was able to track citizens travelling from countries with a history of malaria transmission and immediately refer them for treatment. Special attention was paid to security forces personnel, immigrants and tourists. “A 24×7 hotline was added next for improved tracking and the method of treatment was also changed. Isolation treatment was provided to patients to contain the spreading of infection.” The country’s strong public health system is responsible for the success, says Anura Jayawickrama, Sri Lanka’s health secretary. Early detection and continuous treatment were the key to success. For years, mobile clinics have been used to reach communities, particularly those living in the malaria-affected regions such as the island’s north-west and north-central, he says. Mobile malaria clinics in high transmission areas meant that prompt and effective treatment could reduce the parasite reservoir and the possibility of further transmission, WHO stated in its statement issued after announcing the country malaria-free. Sri Lanka is the second country in Southeast Asia to eradicate malaria. Last year, WHO had declared the Maldives malaria-free. The country has not reported malaria cases since 1982. The country maintained strong epidemiological and entomological surveillance to sustain its malaria-free status for the past three decades. The same strategy is adopted in India but according to K Gunaksekaran, scientist, Vector Control Research Centre, Puducherry, the reason for Sri Lanka’s success is that they were consistent with the effort. “Unlike us, Sri Lanka continued its efforts even after it had brought down the number of malaria cases. We don’t even have regular surveillance for dengue and chikungunya.” |

Recent Posts

The United Nations has shaped so much of global co-operation and regulation that we wouldn’t recognise our world today without the UN’s pervasive role in it. So many small details of our lives – such as postage and copyright laws – are subject to international co-operation nurtured by the UN.

In its 75th year, however, the UN is in a difficult moment as the world faces climate crisis, a global pandemic, great power competition, trade wars, economic depression and a wider breakdown in international co-operation.

Still, the UN has faced tough times before – over many decades during the Cold War, the Security Council was crippled by deep tensions between the US and the Soviet Union. The UN is not as sidelined or divided today as it was then. However, as the relationship between China and the US sours, the achievements of global co-operation are being eroded.

The way in which people speak about the UN often implies a level of coherence and bureaucratic independence that the UN rarely possesses. A failure of the UN is normally better understood as a failure of international co-operation.

We see this recently in the UN’s inability to deal with crises from the ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, to civil conflict in Syria, and the failure of the Security Council to adopt a COVID-19 resolution calling for ceasefires in conflict zones and a co-operative international response to the pandemic.

The UN administration is not primarily to blame for these failures; rather, the problem is the great powers – in the case of COVID-19, China and the US – refusing to co-operate.

Where states fail to agree, the UN is powerless to act.

Marking the 75th anniversary of the official formation of the UN, when 50 founding nations signed the UN Charter on June 26, 1945, we look at some of its key triumphs and resounding failures.

Five successes

1. Peacekeeping

The United Nations was created with the goal of being a collective security organisation. The UN Charter establishes that the use of force is only lawful either in self-defence or if authorised by the UN Security Council. The Security Council’s five permanent members, being China, US, UK, Russia and France, can veto any such resolution.

The UN’s consistent role in seeking to manage conflict is one of its greatest successes.

A key component of this role is peacekeeping. The UN under its second secretary-general, the Swedish statesman Dag Hammarskjöld – who was posthumously awarded the Nobel Peace prize after he died in a suspicious plane crash – created the concept of peacekeeping. Hammarskjöld was responding to the 1956 Suez Crisis, in which the US opposed the invasion of Egypt by its allies Israel, France and the UK.

UN peacekeeping missions involve the use of impartial and armed UN forces, drawn from member states, to stabilise fragile situations. “The essence of peacekeeping is the use of soldiers as a catalyst for peace rather than as the instruments of war,” said then UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, when the forces won the 1988 Nobel Peace Prize following missions in conflict zones in the Middle East, Africa, Asia, Central America and Europe.

However, peacekeeping also counts among the UN’s major failures.

2. Law of the Sea

Negotiated between 1973 and 1982, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) set up the current international law of the seas. It defines states’ rights and creates concepts such as exclusive economic zones, as well as procedures for the settling of disputes, new arrangements for governing deep sea bed mining, and importantly, new provisions for the protection of marine resources and ocean conservation.

Mostly, countries have abided by the convention. There are various disputes that China has over the East and South China Seas which present a conflict between power and law, in that although UNCLOS creates mechanisms for resolving disputes, a powerful state isn’t necessarily going to submit to those mechanisms.

Secondly, on the conservation front, although UNCLOS is a huge step forward, it has failed to adequately protect oceans that are outside any state’s control. Ocean ecosystems have been dramatically transformed through overfishing. This is an ecological catastrophe that UNCLOS has slowed, but failed to address comprehensively.

3. Decolonisation

The idea of racial equality and of a people’s right to self-determination was discussed in the wake of World War I and rejected. After World War II, however, those principles were endorsed within the UN system, and the Trusteeship Council, which monitored the process of decolonisation, was one of the initial bodies of the UN.

Although many national independence movements only won liberation through bloody conflicts, the UN has overseen a process of decolonisation that has transformed international politics. In 1945, around one third of the world’s population lived under colonial rule. Today, there are less than 2 million people living in colonies.

When it comes to the world’s First Nations, however, the UN generally has done little to address their concerns, aside from the non-binding UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples of 2007.

4. Human rights

The Human Rights Declaration of 1948 for the first time set out fundamental human rights to be universally protected, recognising that the “inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world”.

Since 1948, 10 human rights treaties have been adopted – including conventions on the rights of children and migrant workers, and against torture and discrimination based on gender and race – each monitored by its own committee of independent experts.

The language of human rights has created a new framework for thinking about the relationship between the individual, the state and the international system. Although some people would prefer that political movements focus on ‘liberation’ rather than ‘rights’, the idea of human rights has made the individual person a focus of national and international attention.

5. Free trade

Depending on your politics, you might view the World Trade Organisation as a huge success, or a huge failure.

The WTO creates a near-binding system of international trade law with a clear and efficient dispute resolution process.

The majority Australian consensus is that the WTO is a success because it has been good for Australian famers especially, through its winding back of subsidies and tariffs.

However, the WTO enabled an era of globalisation which is now politically controversial.

Recently, the US has sought to disrupt the system. In addition to the trade war with China, the Trump Administration has also refused to appoint tribunal members to the WTO’s Appellate Body, so it has crippled the dispute resolution process. Of course, the Trump Administration is not the first to take issue with China’s trade strategies, which include subsidises for ‘State Owned Enterprises’ and demands that foreign firms transfer intellectual property in exchange for market access.

The existence of the UN has created a forum where nations can discuss new problems, and climate change is one of them. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was set up in 1988 to assess climate science and provide policymakers with assessments and options. In 1992, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change created a permanent forum for negotiations.

However, despite an international scientific body in the IPCC, and 165 signatory nations to the climate treaty, global greenhouse gas emissions have continued to increase.

Under the Paris Agreement, even if every country meets its greenhouse gas emission targets we are still on track for ‘dangerous warming’. Yet, no major country is even on track to meet its targets; while emissions will probably decline this year as a result of COVID-19, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases will still increase.

This illustrates a core conundrum of the UN in that it opens the possibility of global cooperation, but is unable to constrain states from pursuing their narrowly conceived self-interests. Deep co-operation remains challenging.

Five failures of the UN

1. Peacekeeping

During the Bosnian War, Dutch peacekeeping forces stationed in the town of Srebrenica, declared a ‘safe area’ by the UN in 1993, failed in 1995 to stop the massacre of more than 8000 Muslim men and boys by Bosnian Serb forces. This is one of the most widely discussed examples of the failures of international peacekeeping operations.

On the massacre’s 10th anniversary, then UN Secretary General Kofi Annan wrote that the UN had “made serious errors of judgement, rooted in a philosophy of impartiality”, contributing to a mass murder that would “haunt our history forever”.

If you look at some of the other infamous failures of peacekeeping missions – in places such as Rwanda, Somalia and Angola – it is the limited powers given to peacekeeping operations that have resulted in those failures.

2. The invasion of Iraq

The invasion of Iraq by the US in 2003, which was unlawful and without Security Council authorisation, reflects the fact that the UN is has very limited capacity to constrain the actions of great powers.

The Security Council designers created the veto power so that any of the five permanent members could reject a Council resolution, so in that way it is programmed to fail when a great power really wants to do something that the international community generally condemns.

In the case of the Iraq invasion, the US didn’t veto a resolution, but rather sought authorisation that it did not get. The UN, if you go by the idea of collective security, should have responded by defending Iraq against this unlawful use of force.

The invasion proved a humanitarian disaster with the loss of more than 400,000 lives, and many believe that it led to the emergence of the terrorist Islamic State.

3. Refugee crises

The UN brokered the 1951 Refugee Convention to address the plight of people displaced in Europe due to World War II; years later, the 1967 Protocol removed time and geographical restrictions so that the Convention can now apply universally (although many countries in Asia have refused to sign it, owing in part to its Eurocentric origins).

Despite these treaties, and the work of the UN High Commission for Refugees, there is somewhere between 30 and 40 million refugees, many of them, such as many Palestinians, living for decades outside their homelands. This is in addition to more than 40 million people displaced within their own countries.

While for a long time refugee numbers were reducing, in recent years, particularly driven by the Syrian conflict, there have been increases in the number of people being displaced.

During the COVID-19 crisis, boatloads of Rohingya refugees were turned away by port after port. This tragedy has echoes of pre-World War II when ships of Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany were refused entry by multiple countries.

And as a catastrophe of a different kind looms, there is no international framework in place for responding to people who will be displaced by rising seas and other effects of climate change.

4. Conflicts without end

Across the world, there is a shopping list of unresolved civil conflicts and disputed territories.

Palestine and Kashmir are two of the longest-running failures of the UN to resolve disputed lands. More recent, ongoing conflicts include the civil wars in Syria and Yemen.

The common denominator of unresolved conflicts is either division among the great powers, or a lack of international interest due to the geopolitical stakes not being sufficiently high. For instance, the inaction during the Rwandan civil war in the 1990s was not due to a division among great powers, but rather a lack of political will to engage.

In Syria, by contrast, Russia and the US have opposing interests and back opposing sides: Russia backs the government of the Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, whereas the US does not.

5. Acting like it’s 1945

The UN is increasingly out of step with the reality of geopolitics today.

The permanent members of the Security Council reflect the division of power internationally at the end of World War II. The continuing exclusion of Germany, Japan, and rising powers such as India and Indonesia, reflects the failure to reflect the changing balance of power.

Also, bodies such as the IMF and the World Bank, which are part of the UN system, continue to be dominated by the West. In response, China has created potential rival institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

Western domination of UN institutions undermines their credibility. However, a more fundamental problem is that institutions designed in 1945 are a poor fit with the systemic global challenges – of which climate change is foremost – that we face today.